Create your own magic with Web 7.0™ / TDW AgenticOS™. Imagine the possibilities.

Copyright © 2026 Michael Herman (Bindloss, Alberta, Canada) – Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License

Web 7.0™, TDW AgenticOS™ and Hyperonomy™ are trademarks of the Web 7.0 Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Status: Draft

Version: 1.0

License: Apache 2.0

Editors: Michael Herman, Chief Digital Officer, Web 7.0 Foundation

SDO: Web 7.0 Foundation, Bindloss, Alberta, Canada

1. Abstract

DIDIDL defines a transport-neutral, message-type–centric capability description format for agents using using DIDComm.

DIDIDL enables agents to:

- Publish typed tasks grouped under process capabilities

- Describe request, response, and error schemas

- Support machine-readable discovery

- Enable client generation and validation

DIDIDL does not introduce HTTP routing semantics.

1.1 Key Concepts

- Process Capability DID

did:{authority}:{process-name}_{sedashver}/{capability-name}

- Process Capability Task DID

did:{authority}:{process-name}{capability-name}#{task-name}_{semdashverdid:{authority}:{process-name}{capability-name}_{_{semdashversemdashver

- Process Capability Discovery

did:{authority}:{process-name}_{semdashverdid:{authority}:{process-name}_{#disclose-capabilitiessemdashverdid:{authority}:{process-name}#query-capabilitiesdid:{authority}:{process-name}#disclose-capabilitiesdid:{authority}:{process-name}_{{capability-name}semdashver_{#query-semdashvercapabilitydid:{authority}:{process-name}_{#disclose-semdashversemdashvercapabilitydid:{authority}:{process-name}_{{capability-name}#query-semdashvercapabilitydid:{authority}:{process-name}_{#disclose-semdashvercapability

2. Terminology

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Agent | A DIDComm-enabled entity |

| Process Capability (Capability) | A grouping of tasks representing a business or functional process |

| Process Capability Task (Task) | A DIDComm message type representing a callable function |

| Schema | A JSON Schema definition conforming to JSON Schema |

| Process DIDIDL Document (DIDIDL Document) | JSON object conforming to this specification |

Normative keywords MUST, SHOULD, MAY follow RFC 2119.

3. Canonical DID Patterns

| Process Capability Task DID Pattern | Pattern | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Process Capability DID | did: | did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:enrollment_1-0 |

| Process Capability Task DID | | |

| Query/Disclose DID Messsage Types | Pattern | Example |

| Discovery Query Process Capabilities | did: | did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0#query-capabilities |

| Discovery Disclose Process Capabilities | did: | did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0#disclose-capabilities |

| Discovery Query Process Capability Tasks | did: | did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0#query-capability |

| Discovery Disclose Process Capability Tasks | did: | did:web7:user-onboarding |

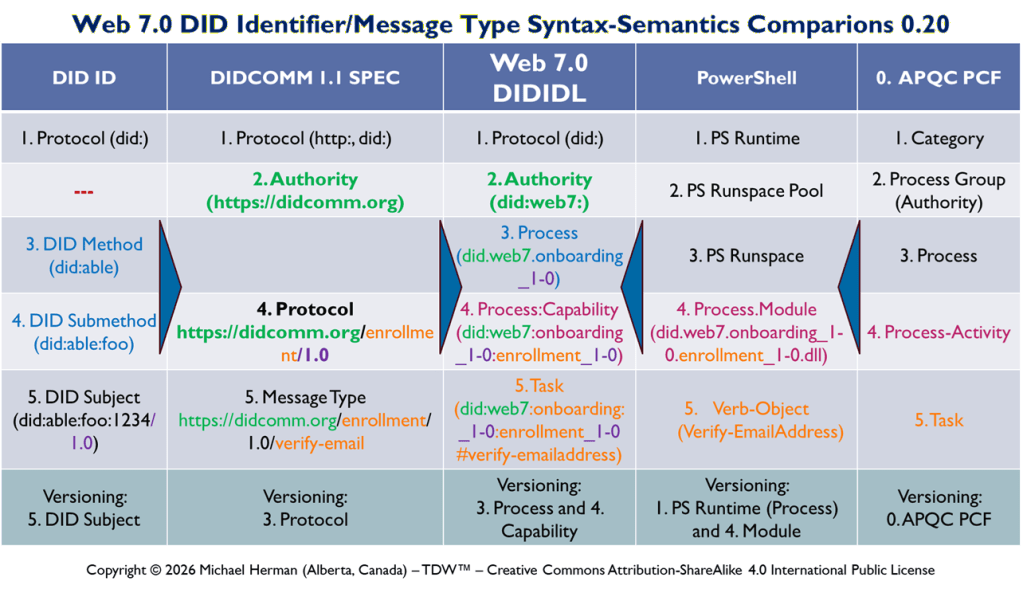

Web 7.0 DID Identifier/Message Type Syntax-Semantics Comparions

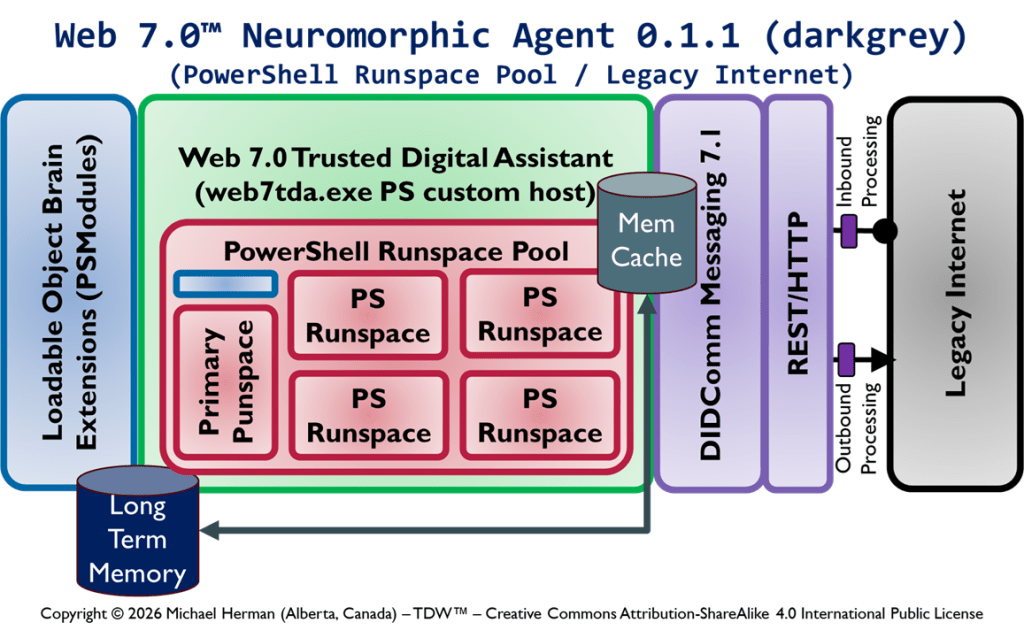

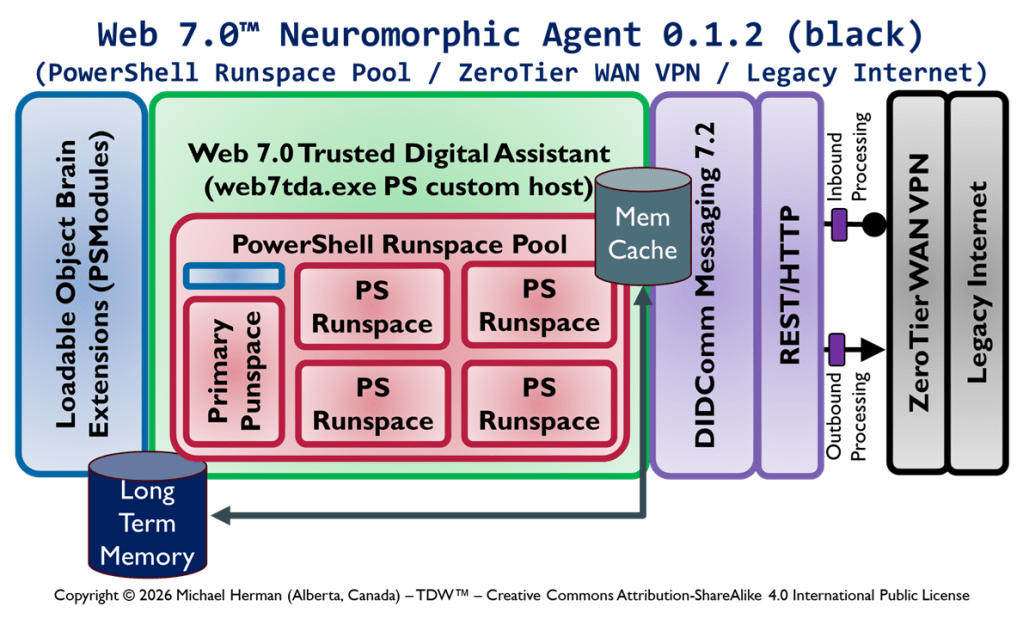

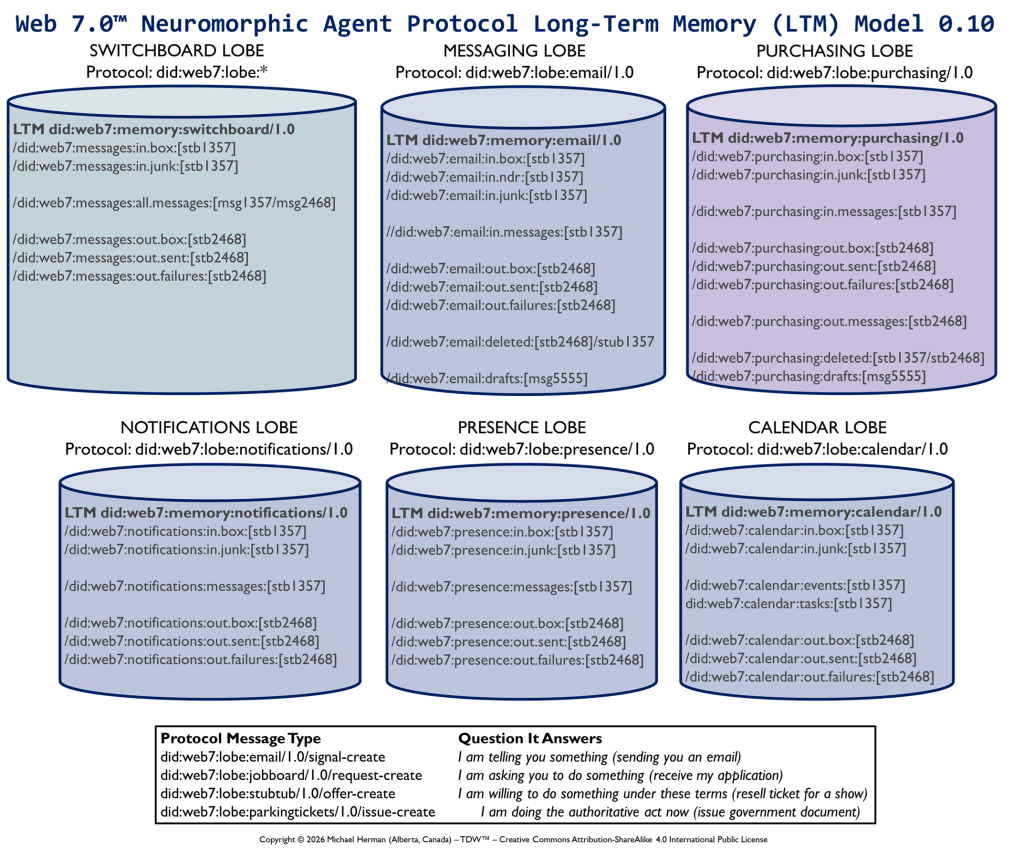

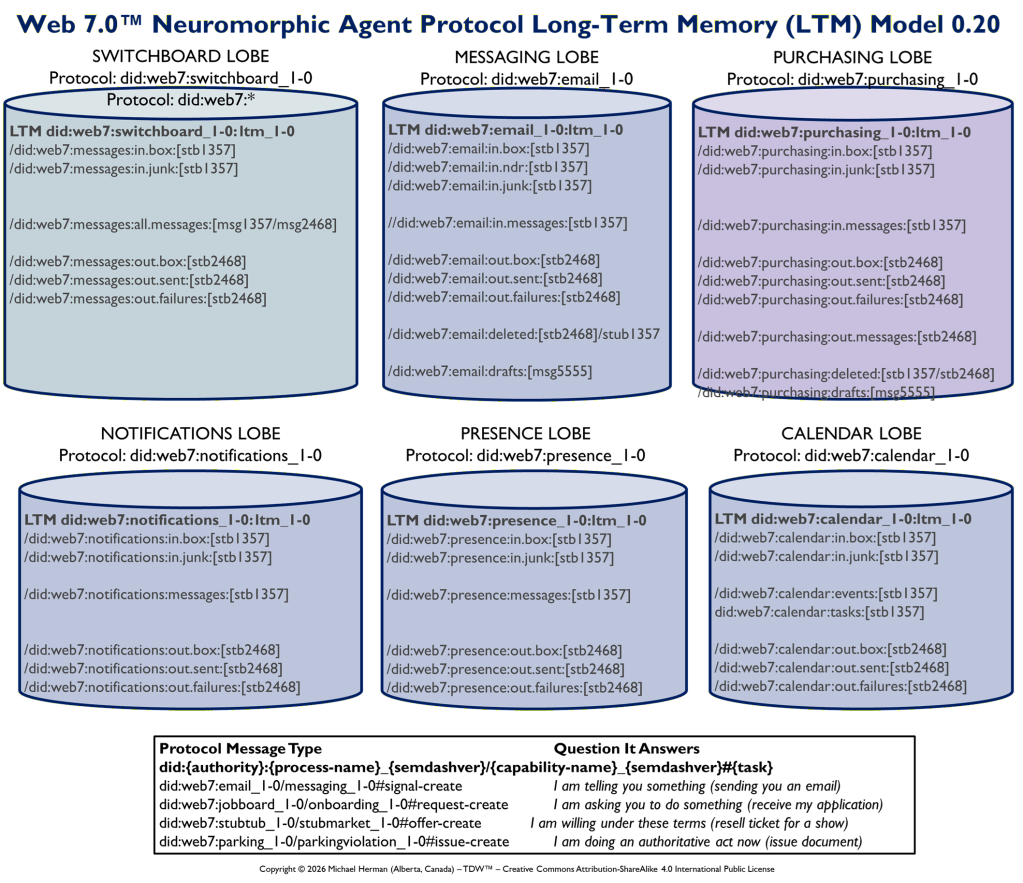

Web 7.0 Neuromorphic Agent Protocol Long-Term Memory (LTM) Model

4. DIDIDL Document Structure

4a. Process Capabilities

{ "dididl": "1.0", "agent": "did:example:agent123", "capabilities": [...], "schemas": {...}}All tasks MUST be nested under exactly one process capability.

4b. Process Capability Tasks

{ "id": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:enrollment", "name": "User Onboarding-Enrollment", "version": "1.0", "description": "Handles user lifecycle initiation", "tasks": [ { "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:enrollment_1-0#create-user", "request": "#/schemas/CreateUserRequest", "response": "#/schemas/UserDto" }, { "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:enrollment_2-0#create-user", "request": "#/schemas/CreateUserRequest", "response": "#/schemas/UserDto" }, { "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:enrollment_1-0#verify-email", "request": "#/schemas/VerifyEmailRequest", "response": "#/schemas/VerifyEmailResponse" } ]}Rules:

- Process Capability DIDs MUST follow the pattern:

did:{authority}:{process-name}_{{capability-name}semdashverdid:{authority}:{process-name}_{{capability-name}_{semdashversemdashver

- Task DIDs are capability-scoped:

did:{authority}:{process-name}_{#{task-name}semdashverdid:{authority}:{process-name}_{_{semdashversemdashver

- Each task MUST belong to exactly one capability

4c. Process Capability Task

{ "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:enrollment_1-0#create-user", "request": "#/schemas/CreateUserRequest", "response": "#/schemas/UserDto", "errors": ["#/schemas/ValidationError"]}Rules:

- Task DIDs MUST be unique within the agent

- Versioning MUST be encoded in the DID

- Request and response schemas MUST be referenced by JSON pointer

5. Discovery Protocol

5.1 Query Capabilities

Request

{ "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0#query-capabilities"}Response

{ "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0#disclose-capabilities", "capabilities": [ { "id": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:userverification", "name": "User Verification", "version": "1.0", "description": "Handles user verification." }, { "id": "did:web7:credential-issuance_1-0/credentialissuance", "name": "Credential Issuance", "version": "1.0" "description": "Handles credential issuance." } ]}5.2 Query a Specific Capability

Request

{"type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:userverification#query-capability"}{ "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:userverification_1-0#query-capability"}Response

{ "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:userverification#disclose-capability", "capability": { "id": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:userverification_1-0", "name": "User Verification", "version": "1.0", "tasks": [ { "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:userverification_1-0#create-user", "request": "#/schemas/CreateUserRequest", "response": "#/schemas/UserDto" }, { "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:userverification_1-0#verify-email", "request": "#/schemas/VerifyEmailRequest", "response": "#/schemas/VerifyEmailResponse" } ], "schemas": {...} }}6. Normative Requirements

- Each task MUST appear in exactly one process capability.

- Process Capability DIDs MUST be unique within the agent.

- Task DIDs are capability-scoped and MUST be unique.

- Union of all process capabilities MUST form a disjoint partition of tasks.

- Schemas included in capability disclosure MUST only include referenced schemas.

- DIDComm authentication MUST protect all DIDIDL exchanges.

- Version changes that introduce breaking schema modifications MUST increment the major version in the DID.

7. Example Complete DIDIDL Document

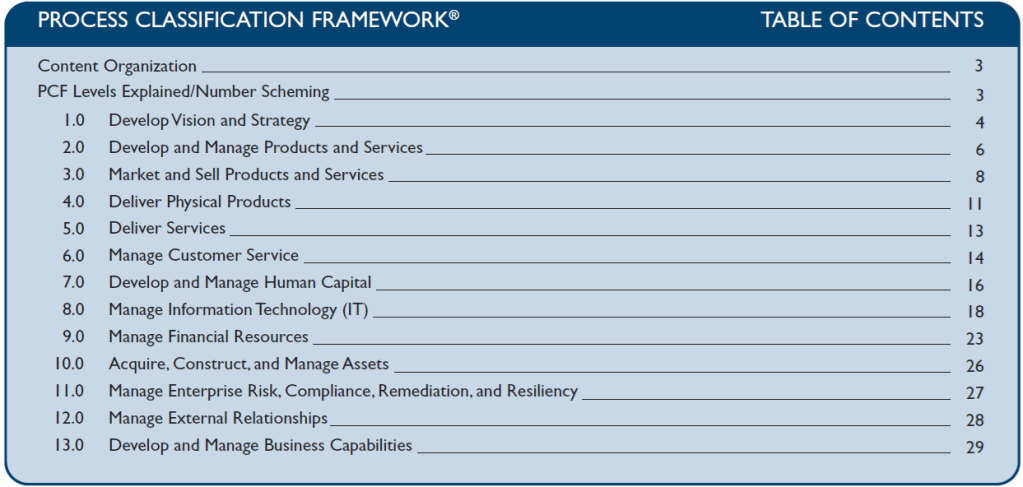

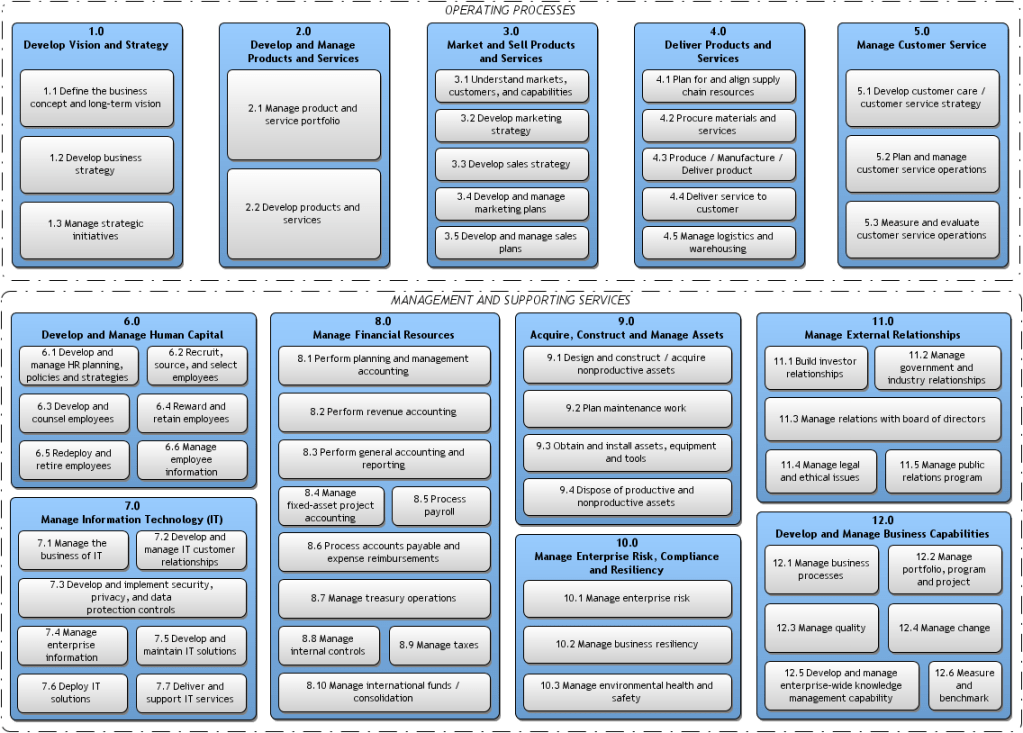

{ "dididl": "1.0", "agent": "did:example:agent123", "capabilities": [ { "id": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:useronboarding", "name": "User Onboarding", "version": "1.0", "tasks": [ { "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:useronboarding_1-0#create-user", "request": "#/schemas/CreateUserRequest", "response": "#/schemas/UserDto" }, { "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:useronboarding_2-0#create-user", "request": "#/schemas/CreateUserRequest", "response": "#/schemas/UserDto" }, { "type": "did:web7:user-onboarding_1-0:useronboarding_1-0#verify-email", "request": "#/schemas/VerifyEmailRequest", "response": "#/schemas/VerifyEmailResponse" } ] } ], "schemas": { "CreateUserRequest": { "$schema": "https://json-schema.org/draft/2020-12/schema", "type": "object", "properties": { "email": { "type": "string" } }, "required": ["email"] }, "VerifyEmailRequest": { "$schema": "https://json-schema.org/draft/2020-12/schema", "type": "object", "properties": { "token": { "type": "string" } }, "required": ["token"] }, "VerifyEmailResponse": { "$schema": "https://json-schema.org/draft/2020-12/schema", "type": "object", "properties": { "success": { "type": "boolean" } }, "required": ["success"] }, "UserDto": { "$schema": "https://json-schema.org/draft/2020-12/schema", "type": "object", "properties": { "id": { "type": "string" }, "email": { "type": "string" } }, "required": ["id", "email"] } }}Appendix B – APQC Taxonomies

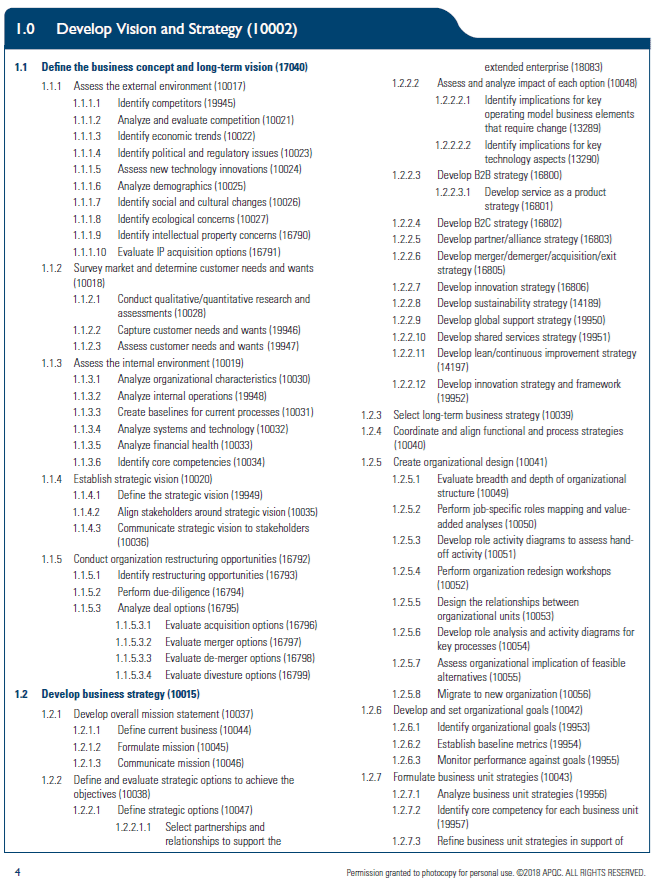

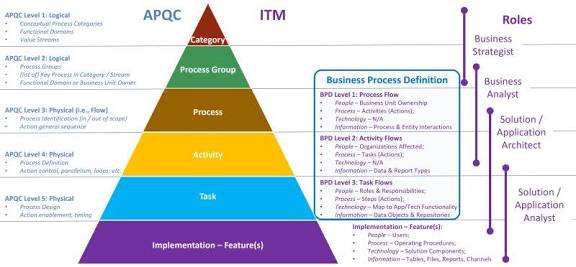

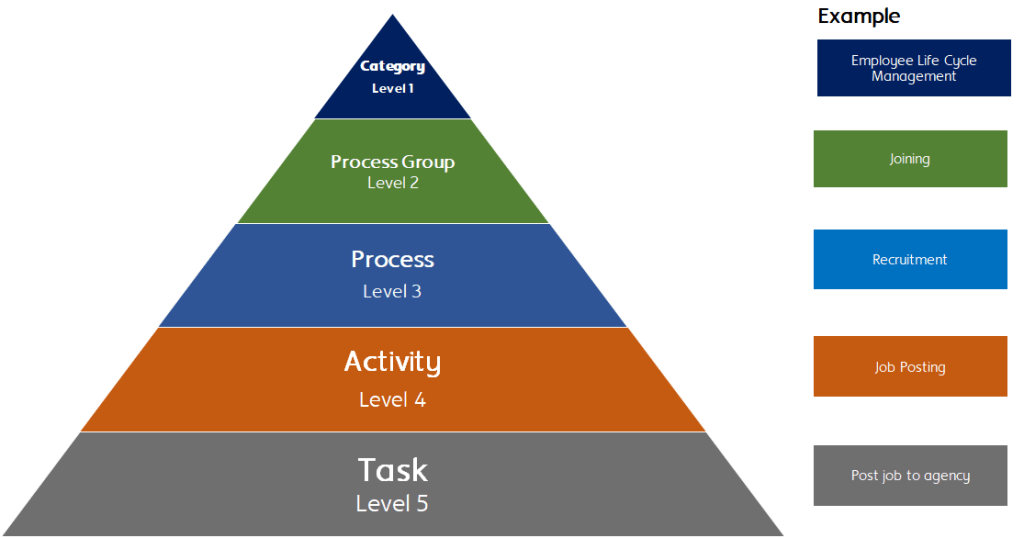

Process Categories and Individual Processes

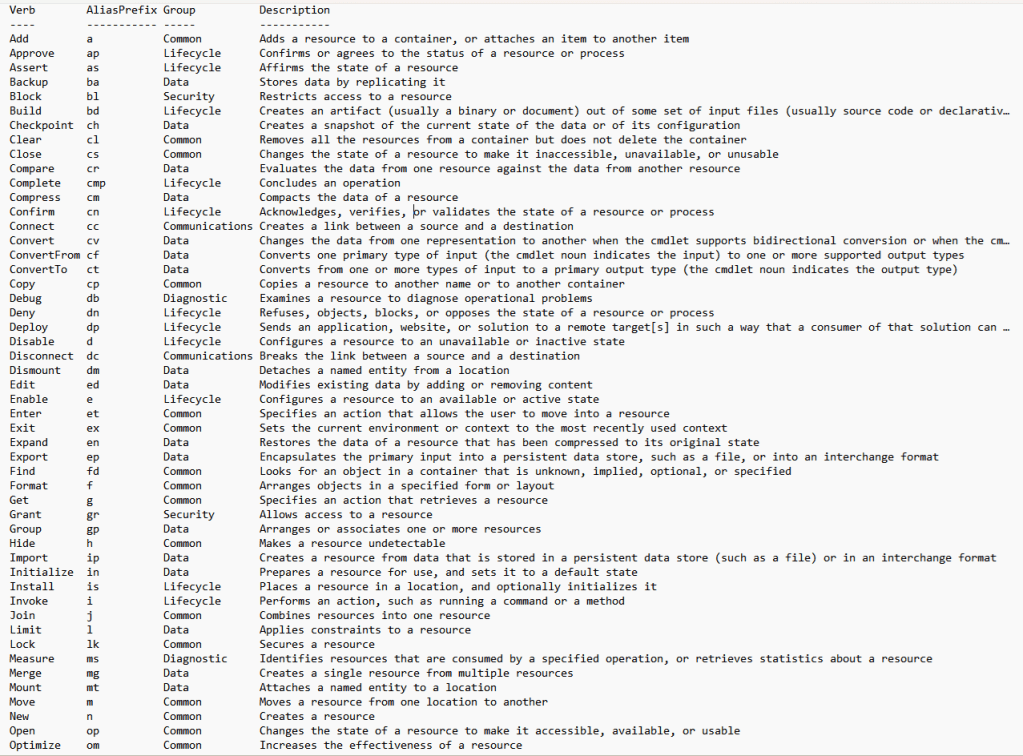

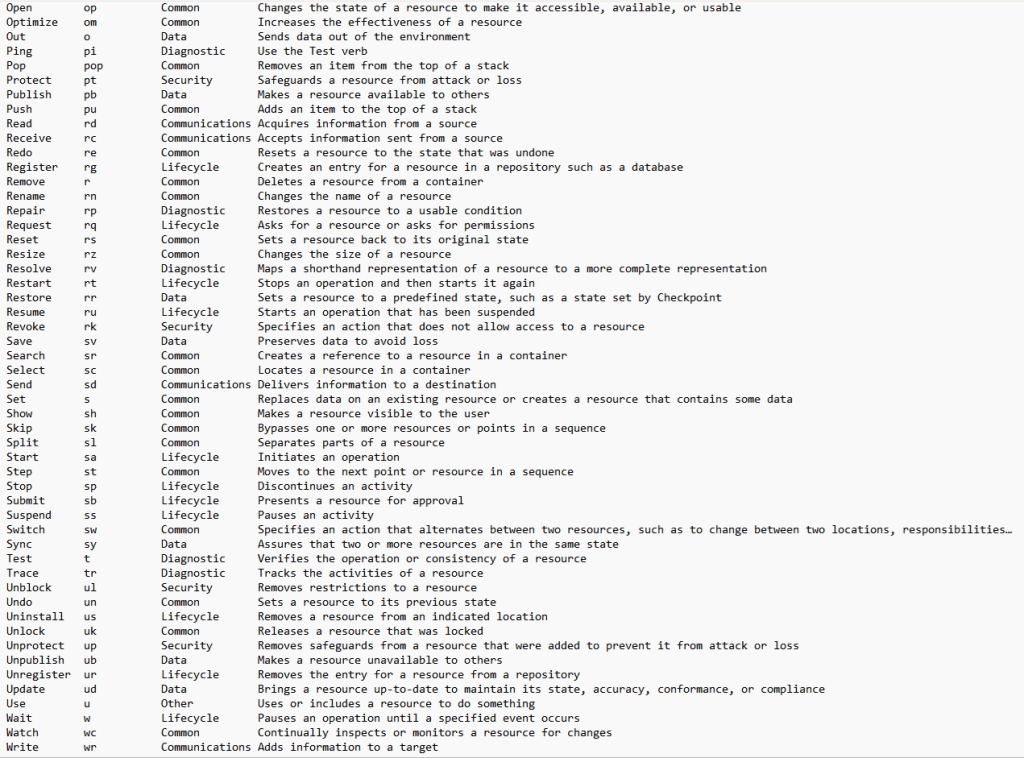

Appendix C – PowerShell Cmdlet Naming Specifications

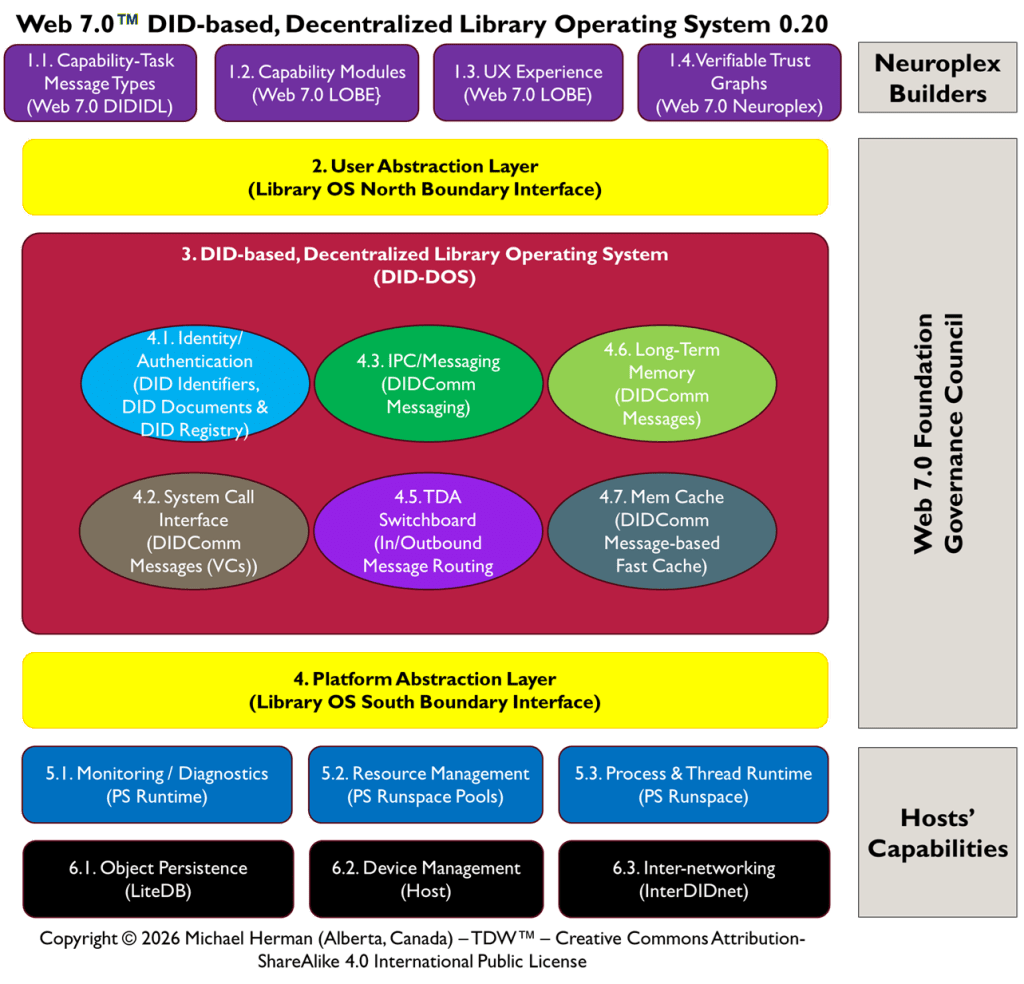

Appendix D – Web 7.0™ DID-based, Decentralized Library Operating System (DID-DOS)